Designing Your People Stack

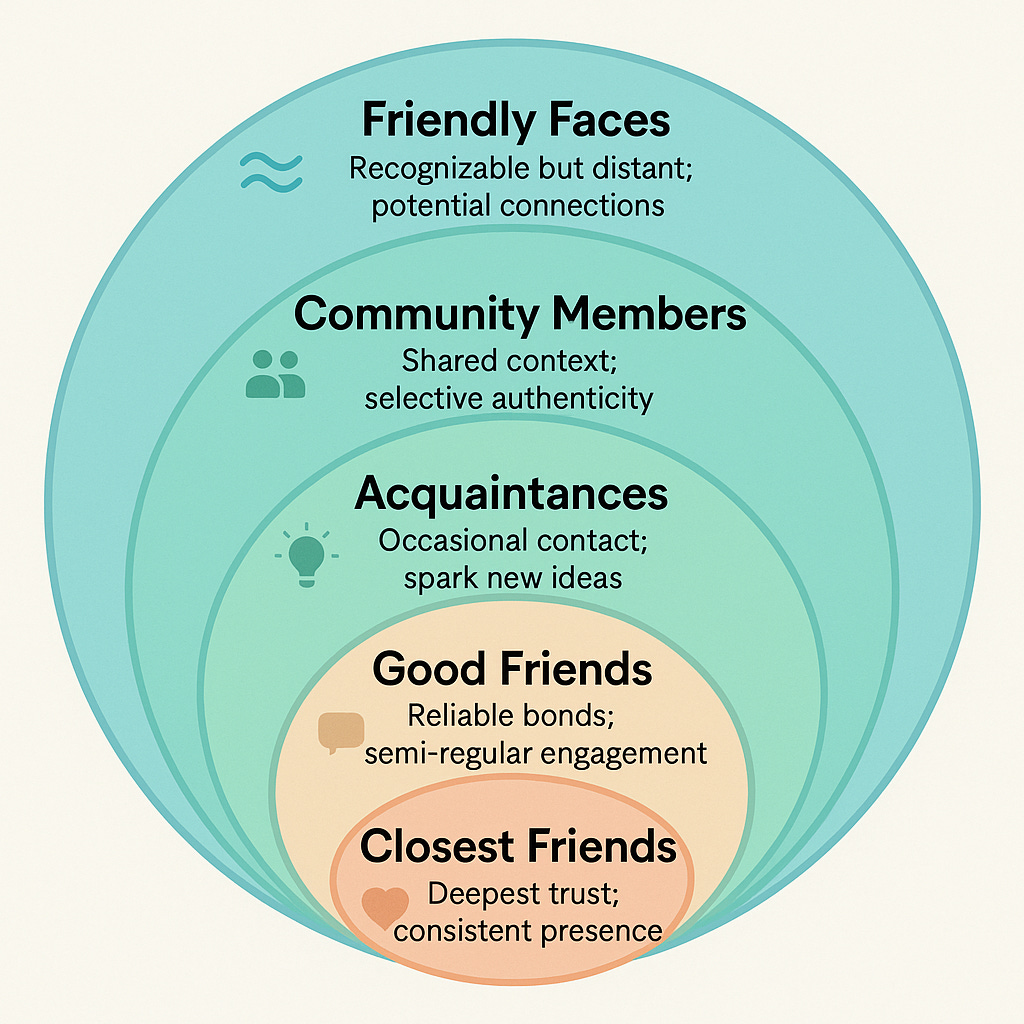

Just like products have user segments, our lives are filled with different types of connections, some deep, others brief but impactful. This week, I’m sharing a framework I use to make sense of it all: the Connection Onion. It’s helped me reduce social pressure and be more intentional about how I show up for others. Plus, in this week’s Behavioral Bytes, we’re taking on a classic cognitive trap, confirmation bias, and how it can quietly derail good product decisions.

🏗️ Frameworks for Everything 🏗️

Takeaway: You don’t need to become close with everyone you meet. By recognizing layers of connection, you can design more authentic relationships and reduce social anxiety.

Most people don't know how to answer the question: "Where does this new person fit in my life?" We meet someone interesting, get along, maybe even have a great conversation—but what happens next? Do we try to become friends? Do we follow up? Let it go? That uncertainty can create subtle pressure, especially for those who meet a lot of new people.

Over the years, I've found myself navigating communities of all types: from the WhatsApp group I run for my apartment building, to organizing research dinners and leading professional associations. I connect with hundreds of people each month. Somewhere along the way, I realized that not all relationships are meant to grow deep—and that's okay. Like product development, human connection benefits from intentional design. Enter: the Connection Onion.

This framework helps me quickly understand the level of connection I have (or want to have) with someone. It’s been one of the best tools for reducing social pressure while increasing authenticity.

Layer 1: Closest Friends

These are the people I can be fully myself with—the ones who add richness and grounding to life.

I trust them with vulnerability and seek out their feedback.

We usually have set rhythms of contact that feel natural and nourishing.

Layer 2: Good Friends

I'm mostly myself, but I may lean into certain aspects of my personality they bring out.

I value their perspective and filter their feedback based on our dynamic.

We aim to connect every couple of weeks.

Layer 3: Acquaintances

Think of these as strong weak ties: real connection, but not yet consistent depth.

I aim to interact every month or so, often through chance or light coordination.

These people often introduce serendipity and new perspectives into my life.

Layer 4: Community Members

We share context, whether through location, profession, or interest.

I show up authentically but selectively, tailoring what I share based on the community norms.

These relationships are often seasonal or tied to shared goals. I try to engage at least quarterly.

Layer 5: Friendly Faces

People I recognize and acknowledge, but with whom I haven’t formed meaningful bonds (yet).

They may eventually move deeper into the onion, or stay on the periphery.

Any feedback or influence they have is filtered through those closer to the center.

How to Use the Connection Onion

Next time you're meeting a group of people—whether at a conference, social event, or new job—ask yourself: "Where might this person fit right now?" Not everyone needs to move inward. If you deeply connect, maybe they land as an acquaintance. If not, they're still a friendly face.

Just like in product development, not every user becomes a power user. But each layer has value.

By using the Connection Onion, you can:

Reduce the anxiety of new social situations.

Design intentional rhythms of engagement.

Give yourself permission to protect your energy while still showing up generously.

🗺️ Behavioral Blueprints 🗺️

Takeaway: Just because it feels right doesn’t mean it is. Confirmation bias tricks us into favoring what fits our current beliefs—and ignoring what challenges them.

Ever started user research hoping to validate a new feature idea—and magically, every insight supports your thinking? That’s confirmation bias at work. It’s the brain’s sneaky way of prioritizing evidence that agrees with our existing views, while dismissing data that says otherwise.

We also see this play out in product metrics. If a redesign bumps engagement in one cohort, it’s tempting to declare success… and ignore that usage tanked in another. Or worse, we spin a narrative to explain it away.

To break the loop:

Seek out devil’s advocate opinions—even (especially) the ones that annoy you.

Ask trusted colleagues to poke holes in your logic.

Do a simple cost-benefit analysis: “What if I’m wrong?”

I do this by actively stress-testing my assumptions with people I respect but often disagree with. The goal isn’t to be right, but to build better products.

What’s one belief you’re holding right now that might deserve a challenge?